11/16/2023 Ventricular Tachycardia and Stroke

You are working in TCC. You get a page that reads, “Triage patient to 5L”. A 65 y/o M with the following vital signs arrives to 5L:

HR: 210

BP: 160/100

RR: 18

O2 sat: 99% RA

T: 37 C

You arrive in the room and see an older male sitting up in bed. He is anxious appearing but nontoxic. He has a normal mental status. He has palpable peripheral pulses and well perfused extremities. Work of breathing is normal. He has faint crackles at the bases.

What would your next steps be?

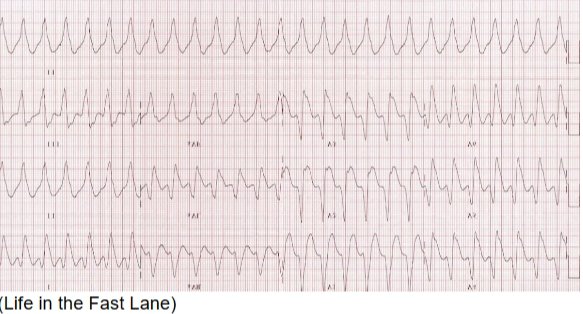

The patient is placed on the monitor and IV access is obtained. Defibrillation pads are placed on the patient and connected to the defibrillator machine. An EKG is obtained which is shown below:

You talk to him and he says that he began to have palpitations, and shortness of breath about 15 minutes ago. He was visiting his mother in the hospital and walked to ED triage. His vitals on the monitor are unchanged since arrival from triage. He has a history of dilated cardiomyopathy, CAD, and hypertension.

What does his EKG show and how would you treat it?

This patient’s EKG is a wide complex, regular tachycardia. This should be assumed to be representative of monomorphic ventricular tachycardia until proven otherwise. It may be a supraventricular tachycardia with aberrancy, but it is safer to assume the rhythm is VT. If you assume it is VT, you will usually be right4 and the treatments you use will be unlikely to harm the patient. However, if you assume it is an SVT with aberrancy, it is possible your therapies will be harmful. The rate of 210 is quite fast for hyperkalemia and is more likely to be VT. Consider hyperkalemia when you have a wide complex tachycardia that is slower, with rates closer to 100-120.

At this point he is stable with a normal blood pressure and it is appropriate to trial medications. It is important to have the defibrillator pads in place in case there is a status change. Adenosine is an acceptable treatment for a stable, undifferentiated, regular, wide complex tachycardia1,2. In a patient with known or highly suspected monomorphic ventricular tachycardia (such as this patient with multiple cardiac risk factors), procainamide, lidocaine or amiodarone are the preferred medications3. However, it is almost never wrong to simply perform synchronized electrical cardioversion, since it is usually safe and has high rates of success.

Ventricular Tachycardia (VT):

VT is defined as 3 or more, consecutive, wide complex (>120 ms) beats at a rate of greater than 120 bpm. In general, VT rates are above 170. Rates significantly slower than this should cause one to question the diagnosis, though it certainly can occur, especially in patients already on anti-arrhythmic. Sustained ventricular tachycardia is when the rhythm lasts for 30 seconds or more. It is important to note that monomorphic and polymorphic ventricular tachycardia are different beasts and have different diagnostic and management pathways.

1) Monomorphic VT (MVT)

This is generally caused by structural heart disease, previous myocardial infarction or adverse drug effects. Acute myocardial ischemia can present with monomorphic VT, though it is less common. Evaluation for patients with MVT should include EKG, troponin, electrolytes and echocardiography (if not recently performed).

Treatment in the acute setting depends on stability. Any unstable patient should undergo synchronized cardioversion at 150-200J. Remember to synch the machine so that it does not administer a shock during a T wave, which could result in degeneration into ventricular fibrillation.

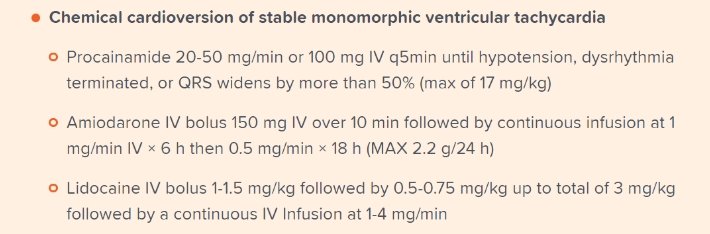

If the patient is stable, pharmacotherapy can be trialed. The PROCAMIO study found that procainamide seemed to be safer and have better rates of ventricular tachycardia termination compared to amiodarone5. Lidocaine is another option. The doses are listed below on this excellent graphic from EMRAP Corependium.

2) Polymorphic Ventricular Tachycardia (PVT)

Whereas MVT patients can be stable on presentation, PVT is nearly always an unstable rhythm. Generally speaking, PVT requires cardioversion. Synchronized cardioversion is preferred, however it may be impossible for the machine to synch appropriately and therefore defibrillation (unsynchronized cardioversion) may be performed.

In stable patients, IV magnesium can be trialed at a rate of 2g over 15 minutes. Once the patient has converted out of PVT, an EKG should be performed to assess the type of PVT. Polymorphic ventricular tachycardia exists in two forms: normal QT and long QT. It is crucial to distinguish these two since the treatments differ significantly.

Normal QT PVT:

These patients should be aggressively investigated for acute coronary syndrome(ACS). ACS is much more likely to present with PVT compared to MVT. Brugada syndrome and catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia (CPVT) are other, less common causes of PVT. If PVT is thought to be due to myocardial ischemia, beta blockers or amiodarone are recommended while the cath lab is activated. Heavy sedation can also be helpful for patients with recurrent VT (ventricular storm). For patients with CPVT beta-blockers are preferred. For Brugada patients with and acute episode of PVT, isoproterenol is preferred.

Long QT PVT:

This is otherwise known as Torsades de Pointe (TdP). It is important to recognize that TdP is a subtype of PVT and not all PVT is Torsades. By definition, TdP must have a long QT. The QTc will almost always be over 500ms in TdP. You won’t know if you are dealing with TdP or normal QT PVT until the patient is out of PVT and you can get a 12 lead ECG. TdP is usually caused by electrolyte derangements, medications or congenital. Once you confirm that the QT is long, magnesium should be given and other electrolytes (calcium, potassium) should be aggressively repleted. It is crucial to NOT give amiodarone to a patient with TdP as amiodarone prolongs the QT. Lidocaine can be used to treat Tdp as it does not prolong the QT and would probably be a better initial antiarrhythmic agent for a patient with PVT if you do not yet know if the QT is long or normal.

Key Points:

Assume that wide complex tachycardia is VT until proven otherwise

Place the defibrillator pads on patients with a concerning arrhythmia early

Synchronize the defibrillator when cardioverting stable patients

PVT with a normal QTc is ACS until proven otherwise

PVT is usually unstable and needs defibrillation

Latent Safety Threats (LST)

This team did an excellent job of identifying a wide complex tachycardia that was concerning for VT. There was strong communication between nursing and physician groups, including robust use of closed-loop communication and shared mental model. It was confirmed multiple times that the sync button was pressed which is critical when performing synchronized cardioversion. There was a short delay in placing pads and hooking up to the defibrillator due to unfamiliarity with equipment so ensure that you know how to do this in every ED you work in! In there is time, we often give sedating medications when performing synchronized cardioversion. Don’t forget to treat this as a procedural sedation and ensure all your equipment (suction, end-tidal CO2, intubation equipment, etc.) is set-up and available.

References:

1) Marill KA, Wolfram S, Desouza IS, et al. Adenosine for wide-complex tachycardia: efficacy and safety. Crit Care Med. 2009;37(9):2512-2518. doi:10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181a93661.

2) Neumar RW, Otto CW, Link MS, et al. Part 8: adult advanced cardiovascular life support: 2010 American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care [published correction appears in Circulation. 2011 Feb 15;123(6):e236] [published correction appears in Circulation. 2013 Dec 24;128(25):e480]. Circulation. 2010;122(18 Suppl 3):S729-S767. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.970988.

3) Meyers H. Pendell, Smith Stephen W., Marill Keith. Tachydysrhythmias. In: Mattu A and Swadron S, ed. CorePendium. Burbank, CA: CorePendium, LLC. https://www.emrap.org/corependium/chapter/recGaV7ak0IY2bMIy/Tachydysrhythmias# h.fqitahkh694h. Updated June 30, 2022. Accessed August 6, 2023.

4) Alblaihed L, Al-Salamah T. Wide Complex Tachycardias. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2022;40(4):733-753. doi:10.1016/j.emc.2022.06.010.

5) Brady WJ, Mattu A, Tabas J, Ferguson JD. The differential diagnosis of wide QRS complex tachycardia. Am J Emerg Med. 2017;35(10):1525-1529. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2017.07.056

6) Ortiz M, Martín A, Arribas F, et al. Randomized comparison of intravenous procainamide vs. intravenous amiodarone for the acute treatment of tolerated wide QRS tachycardia: the PROCAMIO study. Eur Heart J. 2017;38(17):1329-1335.doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehw230