8/31/2023 Trauma

You are working the morning shift in TCC when you receive the following page:

34 y.o female MVC, + LOC, BP 105/65, HR 115, RR 24, 90% RA, ETA 5”

How would you prepare the room for this patient?

As team leader you assemble your team and delegate the roles of primary survey and right sided procedures (trauma/EM resident), left sided procedures (trauma/EM resident), ultrasound (EM resident), airway (EM resident/attending), manual blood pressure (tech), IV access (nursing), medications (nursing) and documenting (nursing). You brief your team on your plan for when the patient arrives.

On arrival, the patient is moved over and connected to the monitor. Her airway is intact and there are absent breath sounds over the LEFT chest. She has palpable peripheral and central pulses. The patient is moving all four extremities spontaneously but not following commands. Her eyes are open spontaneously. She is confused to questioning. Her vitals are as follows:

BP: 100/60

HR: 110

RR: 26

O2 sat: 82% RA

T: 37 C

You take report from EMS. The patient was an unrestrained driver driving approximately 45 mph when she was involved in a head on collision. Her car rolled over and she had a prolonged extraction. They are unable to obtain a coherent history. EMS reports that she had a c-collar in place, was placed on a board and has an IV in the right antecubital fossa. Nursing is able to obtain an additional large bore IV in the left antecubital fossa.

What would your next steps be?

You place the patient on a non-rebreather mask at 15L/min with minimal improvement in her oxygen saturation. You decide to perform a rapid bedside lung ultrasound which demonstrates absent LEFT sided lung sliding and normal RIGHT sided lung sliding. With this information, the left-sided procedures resident places a 28F surgical chest tube with a rush of air on entry into the chest. The patient’s repeat vitals are shown below:

BP: 80/50

HR: 130

RR: 22

O2 sat: 99% on NRB 15L/min

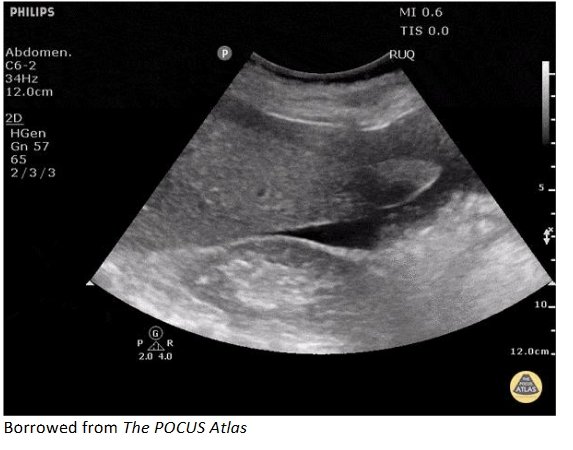

You ask the ultrasound resident to complete the remainder of the FAST exam. An image from the ultrasound is shown below.

What would your next step be?

Given the patient’s hypotension, tachycardia and positive FAST exam, you are concerned that in addition to the patient’s pneumothorax, they are in hemorrhagic shock secondary to intraabdominal hemorrhage. You decide to activate Whole Blood Trauma Massive Transfusion Protocol and administer 2 units uncross matched low titer type O+ whole blood as you and your team complete your secondary survey, which is notable for abrasions to the right face, severe, diffuse abdominal tenderness to palpation with abrasions and bruising, atraumatic upper and lower extremities and no signs of trauma to the back.

Your chest x ray shows the chest tube in appropriate position, with re-expansion of the lung and no other abnormalities. The pelvis x ray shows a normal pubic symphysis without any other obvious abnormalities. The patient’s repeat vitals after two units of whole blood are as follows.

BP: 90/56

HR: 120

RR: 24

O2 sat: 99% on NRB 15L/min

What would your next move be?

You discuss with your team and decide to proceed directly to the OR to manage this patient’s hemorrhagic shock given her hypotension in the setting of a positive FAST exam. While getting the patient ready for transfer you order 1 gram of tranexamic acid IV in addition to 3 grams of calcium gluconate IV. The patient is whisked off to the OR.

Summary and Teaching Points

This was a case of blunt trauma resulting in a pneumothorax with borderline tension physiology and well as hemorrhagic shock from intraabdominal hemorrhage. Management focuses on early recognition of the pneumothorax with physical exam and/or lung ultrasound. A rapid portable chest x ray would be an option, however, with the patient’s borderline hypotension, an argument could be made that they should be decompressed prior to x ray. Following decompression of the pneumothorax the patient’s blood pressure dropped due to continued hemorrhage. The question in this case is not necessarily whether or not the patient needs blood (they do), but what type, how much, and should MTP be activated?

MTP Activation Criteria

Our MTP activation criteria is listed in the attached protocol. Our protocol recommends that at least one of these two criteria be present for MTP activation.

a) Class IV shock and estimated requirements of at least 10 units of blood

b) BOTH substantial acute or imminent blood loss AND a likelihood that substantial blood loss will continue over short term and estimated requirements of at least 10 units of blood

Delay to MTP activation and blood administration in trauma patients with hemorrhagic shock results in increased mortality. In fact, it has been estimated that each minute delay in MTP activation for these patients results in a 5% increase in mortality. However, it can be challenging to predict who really needs MTP early on in the resuscitation when the only information that is available is vital signs, the physical exam and possibly a FAST exam or x ray. There are numerous MTP activation criteria that have been proposed but perhaps the one that best combines effectiveness with ease of use is the ABC criteria, originally derived from a retrospective study performed at Vanderbilt University Medical Center and later validated in a multicenter study. This has four simple criteria and recommends MTP activation if at least two or more are present. The initial retrospective study demonstrated a sensitivity of 75% and a specificity of 86% for the patient requiring at least 10 units of packed red blood cells in the first 24 hours of their resuscitation.

1) Penetrating mechanism

2) Systolic BP ≤ 90 in the ED

3) HR ≥ 120 in the ED

4) Positive FAST

Another tool to identify early hemorrhagic shock is the shock index (SI). The SI is calculated using the simple formula heart rate/systolic blood pressure. The normal value ranges from 0.5 to 0.7. There is some debate regarding exact values, but anything greater than 0.8, and certainly 1.0, should be very concerning for shock. There is some data that a shock index ≥ 1 may actually a better predictor for MTP activation than the ABC score. Consider using these tools the next time you are deciding how to resuscitate your sick trauma patient.

MTP Logistics

Attached is our Wash U MTP protocol. An attending physician, either emergency medicine or trauma, must be the one to activate MTP. The first box of whole blood MTP will bring 6 units of low titer uncrossmatched type O+ whole blood. Following this, the next boxes will contain 6 units of PRBCs, 6 units of fresh frozen plasma (FFP), and 1 standard donor pack of platelets (SDP). Remember that when whole blood is given, Trauma MTP must be activated.

In the blood fridge, located outside of TCC room 3, we have two units of low titer type O+ whole blood, eight units each of O negative and O positive packed red blood cells and six units of A thawed plasma. Remember that after the two units of whole blood have been given, you may need to give PRBCs/FFP/Platelets until the additional whole blood arrives from the blood bank. It is important to communicate with nursing regarding how many blood products have been given and what the resuscitation target is (ex: SBP 90-100) as they can be administered extremely rapidly through the Belmont Rapid Infuser.

Tranexamic acid (TXA)

Our trauma protocol recommends administering TXA to any trauma patient receiving MTP for hemorrhagic shock or if the patient is expected to receive more than two units of packed red blood cells (PRBCs). The dose is 1 gram slow IV push over 10 minutes, followed by 1 gram given as an IV infusion over 8 hours. The evidence for this comes from the CRASH-2 trial and is supported by a Cochrane review. CRASH-2 showed an all-cause mortality decrease in patients with SBP<90, HR>110 or both, who received TXA. It was most was most effective when administered as early as possible (ideally before 3 hours). Remember that TXA is NOT included in the MTP box and you must order this separately.

Calcium

Recent evidence has elucidated the crucial role that calcium plays in our resuscitation of the trauma patient in hemorrhagic shock. One study demonstrated that nearly all trauma patients receiving MTP were hypocalcemic, with approximately 70% of them suffering from severe hypocalcemia. This contributes to their hypotension and coagulopathy (remember calcium is Factor IV in the clotting cascade). Blood product administration (both PRBCs and Whole Blood) can lead to further hypocalcemia as it contains citrate, which chelates calcium. Consider early administration of calcium in your resuscitation, especially if MTP has been activated. Remember that calcium gluconate (usually a dose of 3 grams) is the preferred medication in patients with peripheral access and calcium chloride (1 gram) should generally be reserved for patients with central access.

Other Interventions

Although we cannot mention all the interventions available in this short write-up, we would like to emphasize that we should always remember our systematic approach to these sick patients. Remember to ensure that bilateral IV access is obtained early and if there are challenges consider early intraosseous or central line placement. Remember to intervene on the airway and breathing in addition to circulation issues as the arise and continuously reassess your ABCs.

Control hemorrhage as able in the trauma bay. We should make sure to perform our secondary survey once the primary survey has been completed. Do your best to control your patient’s pain while resuscitating them.

Thank you for reading! We appreciate everyone’s participation in the In-Situ Simulation project and we hope that we can continue to improve as a team to take better care of our patients!

References:

1) Nunez TC, Voskresensky IV, Dossett LA, Shinall R, Dutton WD, Cotton BA. Early prediction of massive transfusion in trauma: simple as ABC (assessment of blood consumption)?. J Trauma. 2009;66(2):346-352. doi:10.1097/TA.0b013e3181961c35. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19204506/

2) Meyer DE, Vincent LE, Fox EE, et al. Every minute counts: Time to delivery of initial massive transfusion cooler and its impact on mortality. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2017;83(1):19-24. doi:10.1097/TA.0000000000001531.

3) Carsetti A, Antolini R, Casarotta E, et al. Shock index as predictor of massive transfusion and mortality in patients with trauma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care. 2023;27(1):85. Published 2023 Mar 5. doi:10.1186/s13054-023-04386-w.

4) Ker K, Roberts I, Shakur H, Coats TJ. Antifibrinolytic drugs for acute traumatic injury. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2015, Issue 5. Art. No.: CD004896. DOI:10.1002/14651858.CD004896.pub4.

5) Roberts I, Shakur H, Coats T, et al. The CRASH-2 trial: a randomised controlled trial and economic evaluation of the effects of tranexamic acid on death, vascular occlusive events and transfusion requirement in bleeding trauma patients. Health Technol Assess. 2013;17(10):1-79. doi:10.3310/hta17100.

6) Schroll R, Swift D, Tatum D, et al. Accuracy of shock index versus ABC score to predict need for massive transfusion in trauma patients. Injury. 2018;49(1):15-19. doi:10.1016/j.injury.2017.09.015.

7) Ditzel RM Jr, Anderson JL, Eisenhart WJ, et al. A review of transfusion- and trauma-induced hypocalcemia: Is it time to change the lethal triad to the lethal diamond?. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2020;88(3):434439. doi:10.1097/TA.0000000000002570.

8) Cotton, Bryan A. MD, MPH; Dossett, Lesly A. MD, MPH; Haut, Elliott R. MD; Shafi, Shahid MD, MPH; Nunez, Timothy C. MD; Au, Brigham K. MD; Zaydfudim, Victor MD, MPH; Johnston, Marla RN, MSN; Arbogast, Patrick PhD; Young, Pampee P. MD, PhD. Multicenter Validation of a Simplified Score to Predict Massive Transfusion in Trauma. The Journal of Trauma: Injury, Infection, and Critical Care 69(1):p S33-S39, July 2010. | DOI:10.1097/TA.0b013e3181e42411.6 / 687%